Clorox to go green with Burt’s Bees acquisition

In the summer of 1984, Burt Shavitz, a beekeeper in

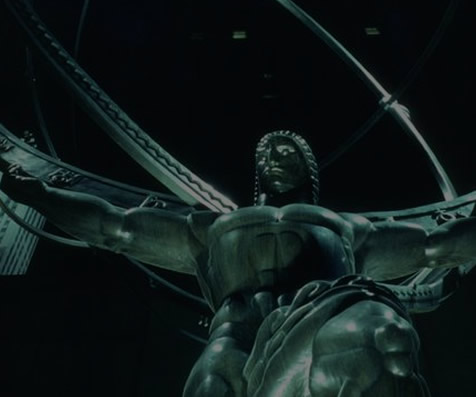

She offered to help Mr. Shavitz tend to his beehives. The two became lovers and eventually birthed Burt’s Bees, a niche company famous for beeswax lip balm, lotions, soaps and shampoos, as well as for its homespun packaging and feel-good, eco-friendly marketing. The bearded man whose image is used to peddle the products is modeled after Mr. Shavitz.

Today, the couple’s quirky enterprise is owned by the Clorox Company, a consumer products giant best known for making bleach, which bought it for $913 million in November. Clorox plans to turn Burt’s Bees into a mainstream American brand sold in big-box stores like Wal-Mart. Along the way, Clorox executives say, they plan to learn from unusual business practices at Burt’s Bees — many centered on environmental sustainability. Clorox, the company promises, is going green.

But not even Clorox can sanitize the details of a fallout between Mr. Shavitz and Ms. Quimby that began in the late 1990s — when Ms. Quimby managed to buy out the bee-man for a low, six-figure sum. She has been paid more than $300 million for her stake in Burt’s Bees, and she spends her time traveling, refurbishing fancy homes in

As unlikely as their journeys have been, Ms. Quimby and Mr. Shavitz are pioneers in an entrepreneurial movement that has lately won the affection of corporate behemoths.

Clorox was willing to pay almost $1 billion for Burt’s Bees because big companies see big opportunities in the market for green products. From 2000 to 2007, Burt’s Bees’ annual revenue soared to $164 million from $23 million. Analysts say there is far more growth to be had by it and its competitors as consumers keep gravitating toward products that promise organic and environmental benefits.

In the last couple of years, L’Oréal paid $1.4 billion for the Body Shop and Colgate-Palmolive bought 84 percent of Tom’s of

Many corporate leaders have sold their shareholders on green initiatives by pointing out that they help cut costs — an argument that is more persuasive now, while energy costs are sky high. But as companies rush to put out more and more “natural,” “organic” or “green” products, consumers and advocacy groups are increasingly questioning the meaning of these labels.

Clorox, for one, will face plenty of skepticism. Environmentalists have long said that bleach is harmful when drained into city sewers. The disinfectant has become a stand-in for jokes about chemicals and the environment, and a new round seems to have begun this fall when the company acquired Burt’s Bees.

“Who likes Burt’s Bees now that it’s been bought by Clorox?” Alison Stewart, a host on National Public Radio, said in November. “You know, just slap some bleach on your lips, it’ll all be good.”

Clorox executives have been fighting what they call “misinformation” about bleach for years. The company says that 95 to 98 percent of its bleach breaks into salt and water and that the remaining byproduct is safe for sewer systems. And Clorox sells many products that have nothing to do with bleach — including Brita water filters, Glad trash bags and

Still, after Clorox agreed to buy Burt’s Bees last fall, scores of customers called Burt’s Bees and accused the company of selling out. John Replogle, the chief executive of Burt’s Bees, says he personally responded to customers who left their phone numbers.

“Don’t judge Clorox as much by where they’ve been as much as where they intend to go,” Mr. Replogle says he told them.